Bicycling on Charlotte streets tends to evoke two reactions. Drivers moan when cyclists slow them down, and cyclists fear for their lives when forced to ride next to cars.

Mixing bikes and cars in the same lane often makes bicycling in Charlotte unsafe. That combination is even more dangerous because bike awareness and safety gets little attention when drivers receive their license and when students take drivers ed in high school.

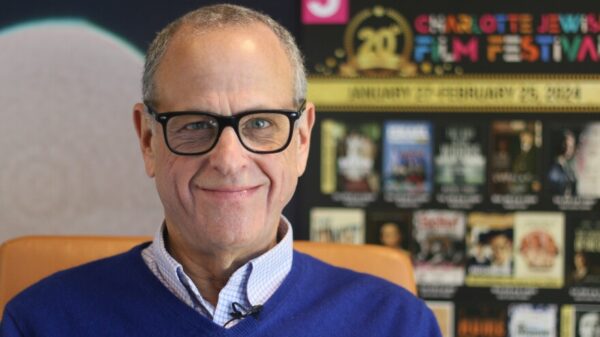

“It’s tiring to be on red alert when cycling,” says Eric Zaverl, an avid bike rider who is former bicycle and pedestrian program coordinator for Sustain Charlotte, a nonprofit group that is advocating to make the city more accessible to cyclists and pedestrians.

Zaverl has cut back his bicycling after several near accidents. He’s concerned drivers are more distracted since the pandemic. “You have to pay attention every second unfortunately right now, just to be safe so you get home.”

Low Bike Safety Rating

Charlotte ranks 97th out of 143 large cities in bike safety, mainly because of a lack of protected bike lanes and a disconnected bicycle network, according to PeopleForBikes, a Colorado-based bike advocacy group. An interactive map created by PeopleForBikes shows how Charlotte’s bike network often doesn’t connect one bike lane to the next, making it difficult for cyclists to find a safe and reliable route.

On April 3, Charlotte City Council member LaWana Mayfield urged colleagues to personally check out Charlotte’s bike network. Motorists are using bicycle lanes as parking spots, she said.

“As we’re building out and connecting, we will have a bike lane that begins nowhere and ends nowhere,” Mayfield said, “as if (the cyclist) is just going to float up in the air to get to the next spot.” Transportation planning needs to include protecting bicyclists, she said.

Street safety affects everyone. “When a street is safer for people who ride bikes, it’s safer for people who drive and safer for people who walk,” said Rebecca Davies, a PeopleForBikes program director.

A lack of visibility and excess speed contribute to the dangers.

“Most vehicles are horizontal, easy to spot … (but) bicycles are vertical. That shape makes it difficult for a lot of drivers to see them,” says Mike Jones, classroom coordinator at Jordan Driving School, which provides driver education for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools “When there’s not a (protected) lane … for cyclists, then you have to really understand, hey, give them space.”

Speeding cars and trucks are big risks for bicyclists sharing the road. Nearly one-third of bike crashes resulting in deaths or serious injuries at non-intersection locations involve motorists overtaking bicyclists, according to the Federal Highway Administration. “The speed and size differential between vehicles and bicycles can lead to severe injury,” the FHWA says.

Speed Requires Separation

The agency’s research shows that as speed and the number of cars increase on roads, bike lanes need to be separated from car lanes. When a road has a speed limit of more than 35 mph, and carries more than 8,000 cars per day, the FHWA recommends at least one protected bicycle lane.

“It’s kind of physics … the faster a big object is moving, the more force it has when it hits something and the more likely someone is to get very hurt, especially … people outside the vehicle,” says Davies.

Pamela Murray, an instructor for CyclingSavvy, a program of the American Bicycling Education Association, says, “Even though the speed limit is 35 miles per hour, people are going way faster.”

She’s avoided an accident after an estimated 70,000 miles on her bike, but adds that a driver “could end my life in an instant.”

To be sure, veteran bike riders like Murray stress that bicycling can be safe with precautions and education. Charlotte bike-related deaths have decreased over the past five years and pale in comparison to auto fatalities. And efforts are underway to make Charlotte streets safer for bicyclists.

A recent $4.4 million grant from Safe Streets for All, which funds initiatives to prevent deaths and serious injuries on the roads, included money to install more separated bike lanes to create safer routes to schools, among other efforts to improve intersection and pedestrian safety.

Gaps in Biking Network

Still, Zaverl says the lack of a city-wide biking network makes it difficult to get around safely.

“It would be like you built a section of interstate highway and it stopped and turned into a dirt road,” he says. “You could never use the interstate. It would be useless.”

Even long stretches of bike-friendly greenways aren’t always usable, he adds. “A lot of them have been built in flood zones,” he says. “If we have a lot of rain…you can’t ride on them because they’re flooded.”

Instead of what he calls “bandaid approaches” of unconnected bikeways throughout the city, Zaverl recommends focusing on corridors that connect a neighborhood or several neighborhoods to a community or employment center such as Uptown.

Poorly maintained bike lanes, lack of neighborhood lighting and constant construction add to the risks, says Miles Fowler, head triathlon coach at Queens University of Charlotte and an avid bicyclist. Debris including glass, gravel and trash often ends up in the bike lane. No street lights make cycling dangerous at night and early morning. And road closings frequently force bicyclists to reroute.

The shortage of protected bike lanes in Charlotte makes it more important for drivers and bicyclists to understand the rules of the road.

Educating the Youth

Bike safety education is particularly important for young people. Between 2015 and 2019, 15-year-olds were the second highest age group to be involved in bicycle accidents, according to the North Carolina Department of Transportation. Those aged 27 were involved in the most bicycle accidents.

Bike safety education is not part of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools health and physical education, although organizations and nonprofits provide outside resources. Elementary schools have access to a program on bicycle and pedestrian safety skills, but it is not mandatory and is dependent on the school’s resources, Murray says.

Bike safety is only briefly mentioned in the North Carolina driver handbook. It details correct hand signals, direction of traffic to ride with, and what turns to avoid when overtaking cyclists. But what turns should you take? What distance should you be from cyclists? Do cyclists have the right of way? These bike safety issues are not addressed in the handbook.

“There should be a rewrite of the driver’s manual,” Zaverl says.

Everyone needs to know the rules of the road, Murray adds. “Whether as a pedestrian, as a cyclist or as a motorist … we’re all three of those at different points in our lives.”

The Risks of ‘Dooring’

“Dooring,” or opening a car door in the path of a bicyclist, is a particular hazard. Yet that danger is not addressed in most states’ driver manuals. North Carolina is one of only nine states without a dooring law, which requires motorists to ensure there is no oncoming traffic before they open their door, according to the League of American Bicyclists.

“Checking the blind spots will let you know who and what’s literally coming beside that vehicle,” says Jones of Jordan Driving School. He advises, “Look twice, look twice, look twice.”

Plenty of distractions keep people from focusing on the road. “You can’t operate a cell phone and drive a vehicle,” Jones says.

A lot of Zaverl’s close calls happened because people were “not paying attention, not stopping when they should,” he says. “They didn’t even realize they almost hit me.”

Since the pandemic, he believes drivers have shorter attention spans, less patience and less awareness of what’s going on around them.

Bicyclists share the blame for unsafe practices. “There needs to be awareness for motorists to look out for cyclists, but cyclists have to look out for themselves as well,” Murray says. The most frequent cause of falls, she adds, is poor bike handling skills.

To stay alert for “dooring,” Murray teaches cyclists to be aware of both the strike zone – the area when they’re going to be hit by the door – and the startle zone. “If the door opens, and you’re startled, you’re going to veer out into traffic, and you’re going to get hit” unless you’re alert and predictable to motorists.

Murray, who says she can get anywhere she needs to go on her bike, believes a city’s bike-safety ranking should be based more on its bicycle education programs. New bike riders often tell her “I’m so scared…. Any amount of talking is not going to convince them” otherwise. But when she rides with them and provides a safe and pleasant experience, “They’ll say, ‘Gosh, that was not hard. And that was not scary.’”

Education on Bicycle Safety

A Safety Quiz for Bicyclists and Drivers

North Carolina Bicycle Safety Quiz

Nearby Classes on Bicycle Safety

Group Bike Rides

PBS ‘My Home: North Carolina’ Video on Overcoming Fear of Bicycling

-

Ellie Fitzgerald of Dublin, Ireland, is a 2023 graduate in multimedia storytelling in the James L. Knight School of Communication at Queens University of Charlotte. She was also a member of the Queens field hockey team.

View all posts