At around 4 p.m., nurse Lydia Bohinski begins her day.

She puts on her scrubs and packs her lunch before heading to a 12-hour shift at Duke Hospital in Durham, only to get home and repeat the same schedule the next day. Or sometimes even for the next five days — a harsh reality for many nurses.

Across North Carolina, nurses at major hospital systems, like Bohinski, are experiencing stress and low morale caused by staffing shortages. Although Novant Health recently fired almost 200 employees for failing to comply with COVID-19 vaccination requirements, low staffing levels may not be as linked to the pandemic as people think.

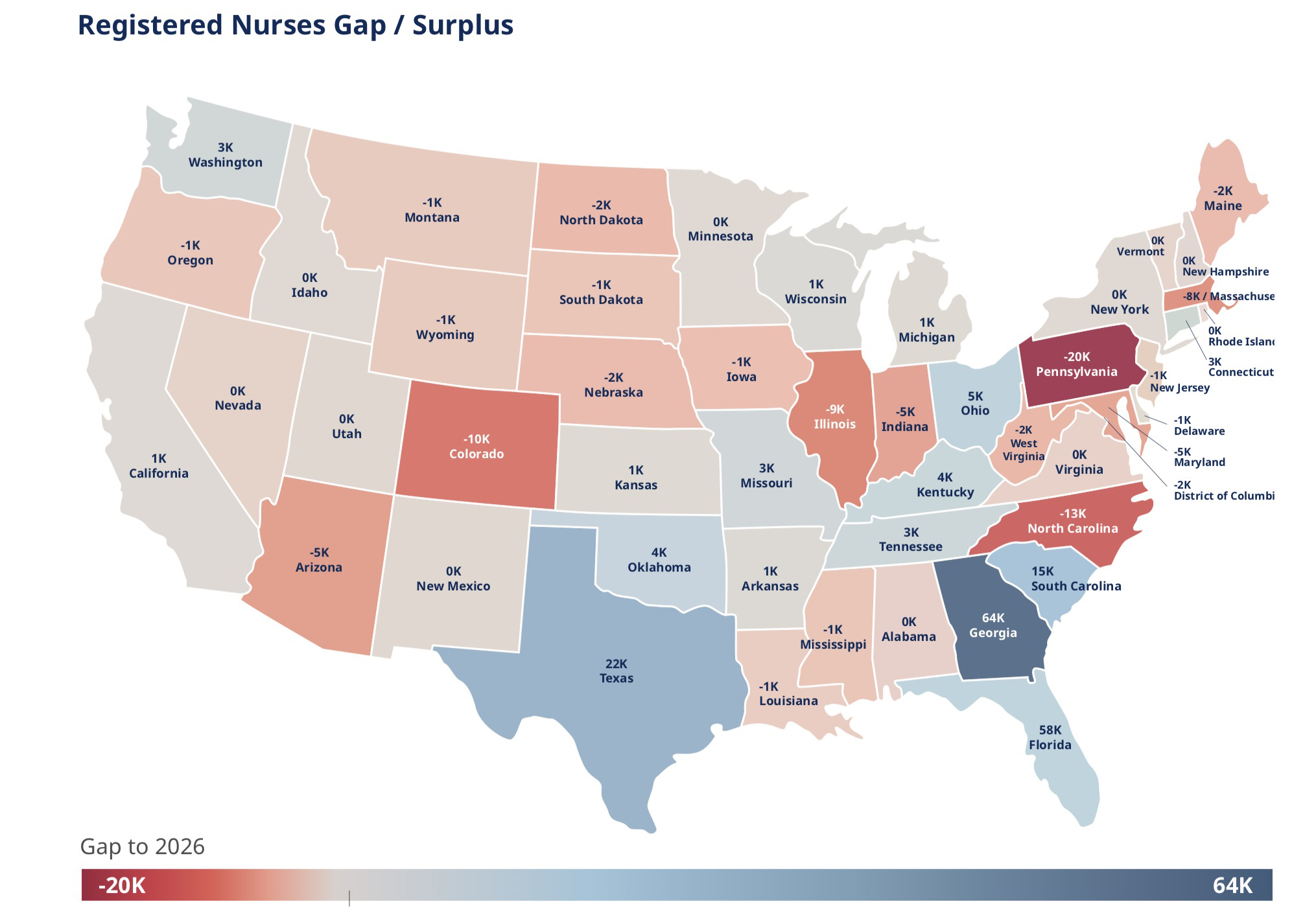

And recent reports from national nursing and professional services organizations indicate nursing shortages will get worse — especially in North Carolina.

“The amount of overtime texts we have gotten in the past couple of months is ridiculous,” Bohinski said recently. “It’s usually twice a day, we get overtime texts. And the problem is, nobody wants to come and work overtime…. Burnout is real among the nurses, among the providers, among the attendings…. You just feel tired all the time and get to a point where you don’t want to go back.”

One of the biggest contributors to nursing shortages is the declining number of educators who can train the next generation. A survey released in September 2021 by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing indicates the vacancy rate for faculty positions increased from 6.5% in 2020 to 8% in 2021. The association reports that U.S. nursing schools turned away more than 80,000 qualified applicants for nursing programs in 2019, mostly because of faculty shortages.

Fewer Nursing Educators Mean Fewer Nurses

To ensure faculty are not overwhelmed when teaching, and can give adequate attention to students, the North Carolina Board of Nursing sets a firm faculty-student ratio of 1-10 for clinical experiences.

“Schools are turning away hundreds of qualified students from East Carolina to Wilmington to your other major programs,” said Linda O’Boyle, a professor of nursing at Barton College in Wilson, North Carolina. “They meet the criteria to get in, but we are limited in pre-licensure education by our regulations of how many students we can take to clinicals. It is a safety issue. We have to protect the public.

“If you don’t have the faculty, you can’t accept the students, it doesn’t matter. If you have seat space, it doesn’t matter,” O’Boyle said.

By turning away students because of the lack of nursing educators, fewer students are graduating and entering the field of nursing.

Even with a 1-10 clinical ratio, O’Boyle said that she and other faculty find that number overwhelming and would prefer a 1-7 or 1-6 teacher-student ratio.

In North Carolina, It Gets Worse

A report issued Sept. 29 by Mercer, a professional services firm focused on workforce changes, retirement and benefits, indicates that North Carolina will be among the five worst states for nursing shortages by 2026. If current projections hold, the firm estimates national demand for nurses will increase by 5% by 2026, and North Carolina will be 13,000 nurses short. Only Pennsylvania is projected to face a larger nursing shortage.

Nursing Faculty Shortages

Of the roughly 125,000 nurses in North Carolina, only around 3 percent are nurse educators, according to statistics from the NC Board of Nursing.

“Faculty salaries are a big thing for universities and community colleges to be able to expand their ability to graduate more nurses and try to meet the demand of nurses in the health system,” said Thompson Forbes, an assistant professor of nursing at East Carolina University.

Even more alarming, according to data from the North Carolina Nurses Association, North Carolina community colleges pay faculty with a bachelor’s degree in nursing $14,923 less on average than they could make in the hospital setting, and faculty with a master’s degree in nursing make $17,618 less than what they could make in a hospital.

Forbes and other nursing faculty have experienced this firsthand.

“I myself transitioned from health systems to academic work, and took a 20% pay cut to do it because it’s what I wanted to do,” Forbes said.

But many nurses cannot afford to take the pay cut.

Dr. Elizabeth Snow, a nursing professor at Randolph Community College in Asheboro, North Carolina, said that without her pension, she would not be able to follow her passion and teach.

“I could do this because my income is supplemented by a pension,” Snow said. “If I was 40 years old, I could not afford it, and as a retired nurse manager, I took a huge cut in pay, huge. If I was 40 years old, I couldn’t go into nursing education.”

Additionally, a 2019-2020 report from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing indicates that the average age of nursing professors with a doctoral degree is 63, which leads many to wonder who will replace those in current teaching positions.

Solutions

To mitigate shortages of nurse educators, many U.S. states are trying to increase nursing instructor salaries to attract more students, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. These initiatives include

$29.3 million in funding from the Maryland High Education Commission to 14 Maryland nursing schools.

An annual $1.5 million allocation to provide five $1,000 tax credits per preceptor (preceptors are a kind of nursing mentor/coach) in Hawaii to increase the number of preceptors in the state. Georgia, Maryland and Colorado have similar programs.

Similar initiatives could potentially be implemented in North Carolina. One possibility is the state budget passed by the North Carolina General Assembly each fiscal year. This past year, a bill was heard in the House to potentially increase pay for direct care workers. Advocates could propose an increased budget to the general assembly in hopes of bolstering pay for the UNC system and for community college faculty.

But for now, nurses like Bohinski hope for better days and less overtime at the hospital.

Queens University News Service

-

Mona Dougani (Author)

Mona Dougani of Charlotte, North Carolina, is a 2021 graduate of the James L. Knight School of Communication at Queens University of Charlotte. Mona served as managing editor of the news service and as an intern with North Carolina Health News and with the Charlotte Journalism Collaborative.

View all posts