As people in California clean up the ashes and start the long road toward recovery, the potential for wildfires elsewhere has been a burning question for other states.

Are urban wildfires a growing threat in more places, including North Carolina?

Jack Scheff, an associate professor of earth, environmental and geographical sciences at UNC Charlotte, says whether or not the Charlotte area is at risk is rather complicated. Scheff has a background in atmospheric sciences, specializing in climate. His research focuses mainly on the effects of climate change.

In general, Charlotte and North Carolina are not typically thought of as fire-prone regions. However, the Southeast experiences more wildfires than any other region in the country. Some parts of the eastern and southeastern United States have experienced a tenfold increase in the frequency of large wildfires over the last forty years, and 45 percent of North Carolina’s 4.7 million homes lie in an area referred to as a wildland-urban interface, an area where human development meets unoccupied land.

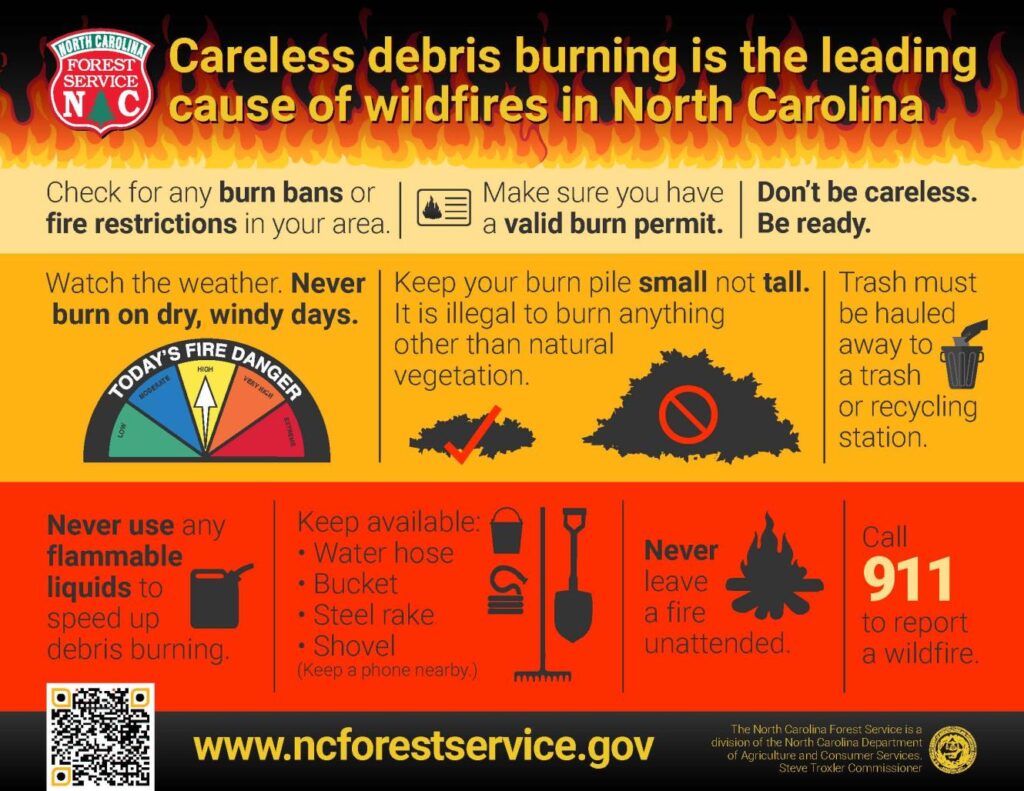

Spring wildfire season in North Carolina officially starts in March. The N.C. Forest Service regularly urges residents to use caution with all outdoor fires, especially when burning yard debris this time of year. The N.C. Forest Service responded to more than 5,300 wildfires across the state in 2023. 99 percent of them were directly related to human activity.

Scheff says there are a number of reasons why the wildfire risk is different here in the Charlotte area. Cities in Southern California have a very different urban forest ecosystem compared to the urban tree ecology we have in Charlotte. Unlike the fire-prone brush forest ecology of parts of the West Coast, the Piedmont region of North Carolina mainly hosts forests of hardwood trees, which burn at much higher temperatures and are therefore less likely to spread or turn into large-scale forest fires. According to Scheff, “This is just fundamentally not as fire-prone an ecosystem … compared to either Southern California or even … eastern North Carolina where there’s a lot of pines.”

The wetter climate also decreases our risk. North Carolina tends to get more frequent rain than is typically expected in Southern California. Scheff says that ultimately North Carolina is less likely to get those tinder-dry fuels post-drought that prompt the wildfires on the West Coast.

The Santa Ana winds also played a major role in last month’s Eaton and Palisades Fires in California. Northeastern University climatologist Chengfei He recently explained the impact of these winds. “As the air moves downhill from the mountains, it gets squeezed and heated up,” said He. “This makes the winds warmer and drier as they blow through Southern California from the Great Basin and through mountain passes on their way to places like Los Angeles and San Diego. The mountains act as a channel that funnels and accelerates the air, creating strong winds.”

Some of the worst Santa Ana winds, combined with an extremely fire-prone forest ecology, created the perfect conditions for a firestorm. North Carolina and Charlotte experience nothing comparable to the fierce Santa Ana winds. “Is it risk? Yes,” says Scheff. “Is it as big a deal as it is in a place in Southern California? I would not think so.”

However, this doesn’t necessarily take into account the effects of climate change, which he says are making wildfire risk worse anywhere.

Scheff says rain is becoming less and less frequent. “The warmer that the climate is, the longer that you have to wait for the next rainstorm, because the warmer air holds more water vapor in it, and it takes longer to get that air re-saturated before the next storm.” The increasing wait between rain events means more time for fuels to dry out – and potentially catch fire. Warmer air also dries out wood and increases the possibility for faster spread.

Climate scientists have also suggested that one of the main culprits of rising temperatures around the globe, steep amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from fossil fuels, could be contributing to fire risk. Carbon dioxide is plant food, which increases plant growth. While the concept is debated, Scheff points out that when these two things collide, drier conditions on increased plant growth is another reason for more potential fire fuel.

Areas of eastern North Carolina, like those along the West Coast of the U.S., have more conifer forests and many of the natural cycles of wildfire have been disrupted by human activity. Around the country, forests have become thicker and denser. Fire safety campaigns have prevented forest fires which serve as nature’s natural forest-thinning technique. Scheff says that by not allowing the forests to burn occasionally, the forests have now grown more fuel, meaning that when fire does break out, it’s much more severe.

“That would apply to us too, probably, our forests are getting denser and more fuel over time and probably that fuel on average is getting drier over time,” he says.

There are several preventive opportunities to manage the risk of wildfires. Controlled burning, deliberate logging of smaller trees, and grazing by animals all help mitigate the chance for wildfires.

Ultimately, while wildfires might be a valid concern for some Charlotteans, Scheff says it is not one of the area’s top concerns and climate change will challenge our understanding of fire risk in the area. “If you do nothing, then nature comes back,” says Scheff.

-

Sofia Bartholomew of Charlotte, North Carolina, is a conservation biology, creative writing, and history major in the College of Arts and Sciences at Queens University of Charlotte. Sofia is also a performance usher at Queens University’s Sarah Belk Gambrell Center for Arts and Civic Engagement. She was awarded a regional Gold Key and an Honorable Mention award for writing in the 2024 Scholastic Art and Writing Awards.

View all posts