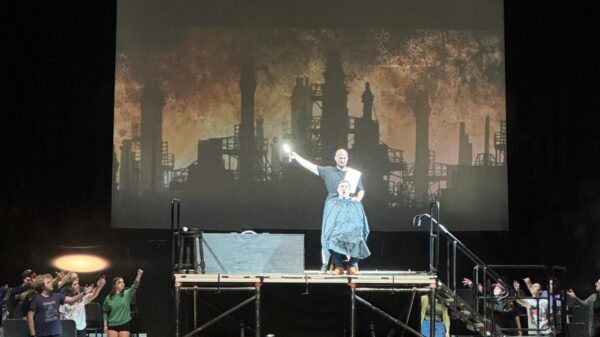

Conversations with artist Shepard Fairey about his latest works in North Carolina reveal the role of murals in civic life, how growing up in the South affects his work, and how impressed he is by recent collaboration among Charlotte artists and institutions.

Fairey grew up in Charleston and became famous in 2008 for his work on the Obama “Hope” campaign poster. Since then, he has painted street murals throughout Europe and North America. His latest works in the Charlotte area, two murals at The Mercantile retail center in Rock Hill and another on the Gambrell building on the Queens University campus, build on themes of activism and justice.

“Art is often an underutilized and underappreciated tool of civic engagement and activism,” Fairey said after completing the Charlotte-area murals in late October. “In less purely aesthetic and coded ways, a way of more literally saying this is — ‘me sharing my humanity in trying to connect to your humanity.’”

The scale and context of public art provide it with a power that many other art forms lack, Fairey said, and combine that power with an almost intimate way of establishing human connection and identity.

“We are especially conditioned to see public space as dominated by commercial advertising and government signage and there isn’t much room for individual expression,” he said. “There isn’t a lot of true democracy even in these realms that are considered community-originated public forums.”

Growing Up in the South

It’s impossible to avoid influence from your origins and the people you’ve been around, Fairey said. “Growing up in Charleston, I liked a lot of things about it and then I realized that I didn’t like a lot of things about it. But I didn’t have perspective.”

As a student, Fairey attended Porter-Gaud, a Charleston private school where there was a very specific model of success, he said, that he slowly realized he did not want to follow. In high school, he turned toward subcultures of punk rock music and skateboarding — cultures that said, “if the mainstream doesn’t offer us an opportunity, we just make our own opportunity.”

The do-it-yourself ethic and bonds he made within these communities made him think about the value of creative adaptation, and how communities depend on shared support.

In high school, he transferred to Idyllwild Arts Academy in California, where his teachers made him feel like a less-experienced peer, rather than a subordinate. He later graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design.

As an adult, he still carries lessons of generosity and community learned in Charleston. In some of the large cities he finds himself in, Fairey said, he doesn’t always find the values of good Samaritans.

“If I got a flat tire in Charleston, people would check to see if I needed help,” he said. “Even if it didn’t manifest in the deeper structural ways I would like, people would always give a gracious toast at a meal and try to make everyone in the room feel valued.”

Fairey said he tries to employ this sense of community and good manners within his company, relationships and work.

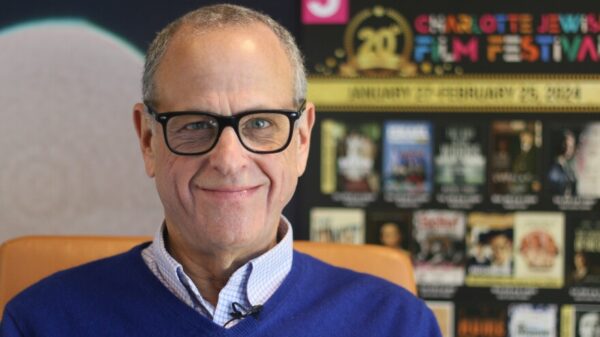

Collaboration with Charlotte Institutions

Fairey is impressed by the everyday sense of collaboration among artists and institutions in Charlotte. The work of artists and city leaders to create the Black Lives Matter street art on South Tryon in June 2020, he said, is a great example.

Mike Wirth, an art professor at Queens and co-founder of the Talking Walls Charlotte Mural Festival, points to several murals that provide examples of civic collaboration. For example, Abel Jackson’s “River of Life” mural on Beatties Ford Road was supported by a City of Charlotte Placemaking Grant. Others include “The Last Black Starfighter,” by Marcus Kiser and Jason Woodberry, on West Trade Street near Johnson C. Smith University; the “Climate Change Mural” by Irisol Gonzalez on 77 Center Drive near Tyvola Road; and “Booker T” by Georgie Nakima, at Booker Avenue and Beatties Ford Road.

Additionally, the work of muralist Marcus Kiser inspired the style of chapters in the graphic novel “Pandemic: Stories of COVID-19.” Kiser created two chapters and recruited many of the book’s graphic artists. The book was produced in a collaboration among artists, the Charlotte Journalism Collaborative and the BOOM Charlotte art organization.

Beyond collaboration among artists and city organizations, Fairey said, universities also play a key role. “Having allies in universities is really important because that is the period of time when people really become who they will be in life. So to have some impact on their ideals, their critical thinking, to me is valuable.”

Fairey, who is now 50, has some insight about his younger self.

“Teenagers are just dissatisfied, and I am still dissatisfied in a lot of ways. I think I channel my dissatisfaction in ways that are more constructive now,” he said. “At 23 I was still finding my identity, but I was definitely a rebel, I was definitely suspicious of anything that came from the mainstream or dominant power structures…. When you’re in your early 20s it’s a time when you are most figuring out how you’re going to synthesize those feelings of teenage rebellion with the need to be a functional member of society, capable of earning a living. So I was confused at 23. I didn’t know how I was going to reconcile those things.”